History of Genome Assembly

Significant Milestones

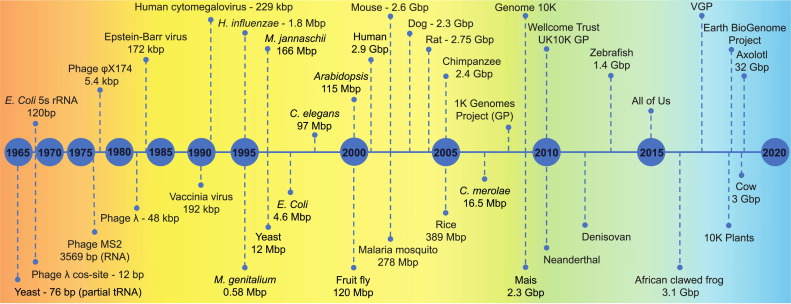

1977 - Sanger et al. assemble the first complete genome (5375 bp) of an organism, specifically a bacteriophage.

1995 - Fleischmann et al. assemble the first complete genome (1.8Mb) of a free-living bacterium, Haemophilus influenzae. This was done using the IGR (Institute for Genomic Research) Assembler.

1998 - The first complete genome (97Mbp) of a multicellular organism, C. elegans, is assembled. The assembly was done using the BAC-by-BAC strategy with Phrap software.

2000 - Myers et al. assemble the Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly) genome (116 Mbp). The assemble was done with the WGS Assembly strategy and Celera Assembler software.

There are many more sequencing projects involving a diverse variety of living organisms.

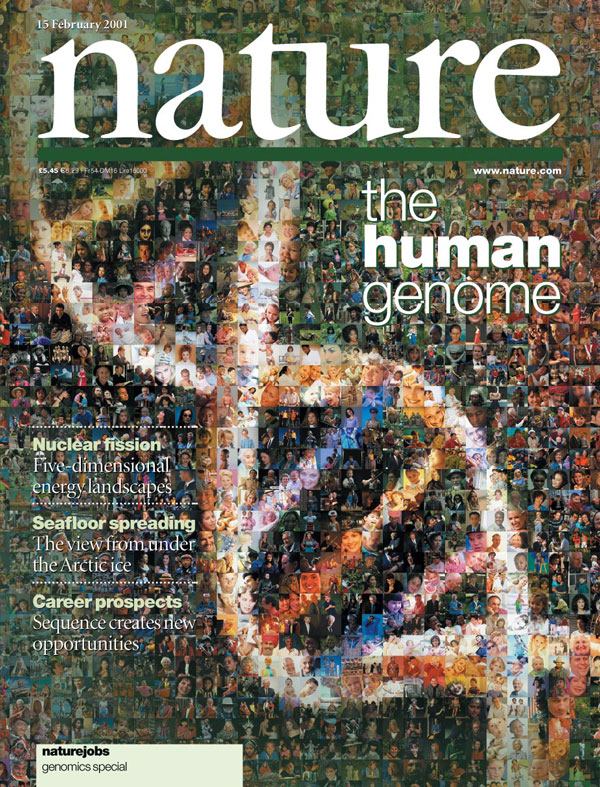

The Human Genome Project

There were both public and private efforts to complete the human genome sequence. In 1990, The Department of Energy and the National Institutes of Health began funding a $3 billion project to assemble the human genome from millions of small DNA fragments. The project was officially announced as complete in 2003. In 1998, Craig Venter and his company Celera Genomics began a privately funded effort to sequence the human genome, costing about 300 million dollars. Later on, the courts established that human genes could not be patented.

Though the Human Genome project was “completed” in 2003, the project was actually only 99% finished, with the remaining 1% consisting of highly repetitive DNA (heterochromatic regions, centromeres, telomeres, tandem duplications) that was difficult to assemble with the technology at the time. Later, advancements in technology were able to produce longer reads, making the sequencing of highly repetitive DNA much easier. Crucial technological advancements included:

- 120x Nanopore

- 70x PacBio

- 30x PacBio HiFi

- 50x 10X Genomics

- 100x Illumina

- 35x Arima Hi-C

- BioNano optical map

- PacBio Iso-Seq

Technologies like Nanopore and PacBio were able to produce complete long reads, while 10X single cell sequencing allowed for the analysis of DNA from individual cells. Arima Hi-C was able to map the three dimensional architecture of the genome, helping scientists understand gene regulation. Optical mapping techniques like Bionano provided a large-scale view of DNA, helping to order fragments, estimate gap sizes, and fill in gaps by detecting structural variants.

As a result of these new technologies, the human genome was able to be sequenced from telomere to telomere. Previously unresolvable regions like centromeres could now be successfully assembled, and previous gaps on the genome were filled. Technology has improved so much that in 2023, scientists were able to fully sequence a human Y chromosome (known to contain an extremely high proportion of repetitive DNA sequences).

Genome Assembly

The objective of genome assembly is to determine the sequence of nucleotides in a DNA molecule or an entire organism’s genome. To begin the process, you need many copies of your DNA sequence. The sequences will next need to be fragmented (broken down into smaller sections), and then those fragments can be processed by technology to produce reads (short sequences of nucleotides). Afterwards, algorithms use the reads to assemble the original sequence through three main steps: Overlap, Layout, and Consensus.

Overlap

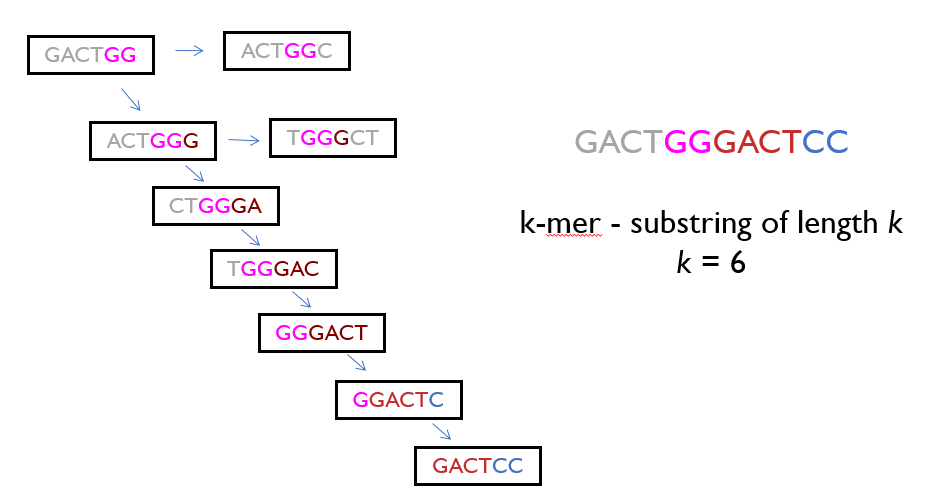

Reads can be broken down further into k-mers (substrings of length k), and these k-mers are used to find overlaps between different reads. For example, if two reads share a significant number of k-mers, it’s a strong indication that they overlap.

Layout

The reads are then arranged in a graph (often a de Bruijn graph) so that the path through the graph represents the assembled sequence. The path should explain every read while maximizing overlaps.

Consensus

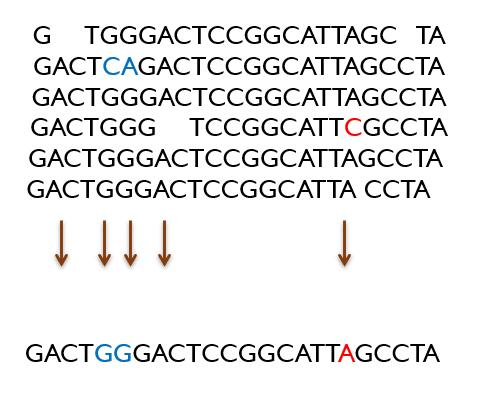

All the assembled sequences are then compared to one another. If there are different nucleotides at a certain position, the most frequent nucleotide is used to reach a consensus. This helps to correct errors that might have occurred earlier during the sequencing process, producing a final DNA sequence.